Efforts by the government to distribute land at a price wasn’t as successful as it had hoped. (See last post) However, the government’s efforts to let people settle land and then pay for it were opposed by people in the East, who thought a huge number of workers would leave. Southerners were afraid that a large number of people in western territories would lead to the creation of free states , since they assumed most small farmers would oppose slavery.

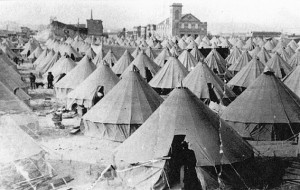

After the South seceded, the government passed the Homestead Act in 1862. The law allowed a homesteader to file an application for a 160-acre plot of surveyed land, farm and improve it for five years, and then file for a deed of ownership. There were certain requirements within this framework that unscrupulous people tried to make a profit from (like whether the 12 X 14 house they had to build could be in inches, since the law didn’t specify).

What kept fraud down was the fact that free or not, land in the western territories was hard to conquer. My next post will describe some of the difficulties settlers faced.

________________________________________________________________________