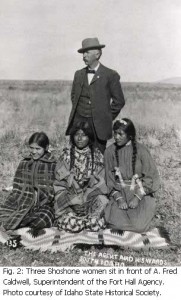

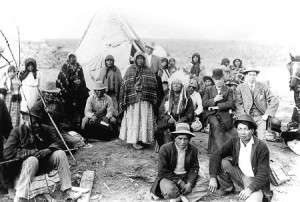

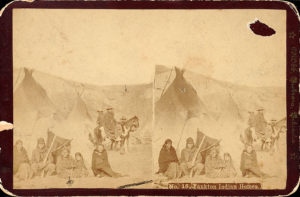

The Native American patients at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians were at a disadvantage compared to their white counterparts at other asylums; Native Americans had few rights and little voice in what authorities might choose to do to “help” them. Another group with a similar disadvantage was America’s African-American population.

The Crownsville Hospital for the Negro Insane in Maryland was constructed in 1910, and used as a warehouse for the mentally ill, criminally insane, the feeble-minded, epileptics, children, and others who exhibited troublesome behaviors in society. Patient labor was used to help build the facility, and patients were later used in the institution’s workforce to help keep costs under control.

Like many asylums, the one at Crownsville began on a high note of modern conveniences and a commitment to provide psychiatric care for its patients. Overcrowding quickly became a problem. Children slept two to a bed, adults on mattresses on the floor, and some patients lived in a windowless basement. Medical care became equally appalling. Doctors tested drugs on patients without their consent, and patient cadavers were sent to Baltimore for medical research without the consent of families.

The facility closed in 2004, with its future use still under consideration. In my next post, I will discuss the asylum’s juvenile patients.