In his first official report, when the asylum was new and Superintendent Oscar Gifford had fewer than 20 patients, his glowing words probably did not fall too fall short of what was actually going on at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. “The patients are provided with a healthful, well cooked diet” which included eggs, milk, and fresh vegetables grown in the asylum garden. It is not too difficult to believe that a cook could have provided such meals for the relatively small staff and patient population that existed, and at that point, actually took great pride in her part of the new enterprise.

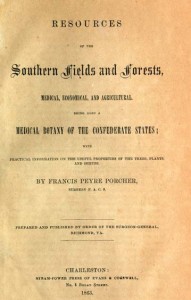

“The medical treatment has been tonic in character excepting in such cases and at such times, where antispasmodics, eliminants or other special treatments were indicated. . . . .In the treatment of melancholia an unlimited amount of patience and forbearance is required to insure good results, and our work in this regard I think has been a success. The epileptics require constant oversight, but the convulsions have been largely controlled, not alone by sedatives but by tonics . . . .”

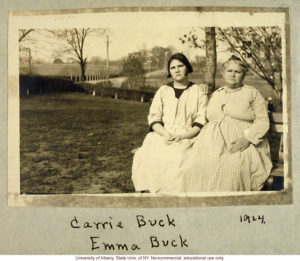

Though no one likely wanted to come to the asylum, patients probably did receive far more individual attention from the full-time physician on staff (Dr. John F. Turner) than they would have received at any reservation.

______________________________________________________________________________________