Native Americans generally ate a healthy, varied diet when they were free to do so. Foods included wild berries, fishes of all kinds, pigeons and ducks, bread made from nutritious wild grasses like pigweed and dropseed, and sweeteners from agave and maple syrup. Native Americans drank sassafras tea and broth thickened with corn silks, along with many other soups and drinks. Many explorers were impressed by the physical development of Native Americans and saw much to admire in their athleticism and endurance. Continue reading

Category Archives: Indian tribes

Spring Planting

Native American tribes pursued different lifestyles depending on where they lived. Though most did not farm in the European sense of having large, established plots owned by one owner/family group, farming was a well-developed practice in many areas. Native Americans typically moved their farming operations every few years, allowing their agricultural land to regenerate after intense use. New plots had to be prepared from either virgin wilderness or substantially overgrown land, so preparation was started far in advance of any actual shift to a new field.

Men first girdled trees by chopping bark all around the trees’ bases; the trees eventually rotted and fell or dried out and stood in place. Men returned to the area at least a year later–perhaps more–and gathered all the brush and fallen wood. They piled this material along with chopped saplings around the trees which had dried in place, and set fire to it. Though the method sounds wasteful today, it actually fertilized the earth with rotted wood and ash. The method also saved a great deal of labor, since girdling and burning trees was much easier than chopping them down and hauling them away.

The communal culture of most tribes usually carried over to farming, so these large fields would have provided food for everyone. Family groups may have also worked smaller plots for personal use.

Division Doesn’t Stop with the U.S.

During the Civil War, Native Americans fought for both the Confederacy and the Union. Tribes found it difficult to decide which government to trust, since their experience had shown that almost all white men in policy-making positions were untrustworthy. Not all tribes were united in or satisfied with their leaders’ decisions, but Native American soldiers could be depended upon to fight bravely and remain loyal to the cause they had chosen.

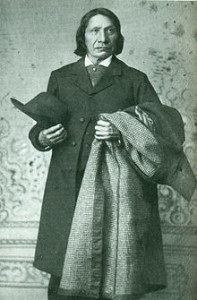

Stand Watie was born in 1806 in present-day Gordon County, Georgia. He signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1836, in which a group of Cherokees surrendered their land in the east in exchange for land in the west (Oklahoma). Because he had signed this treaty and given away tribal land, Watie was under a death sentence from the group of Cherokees who had disagreed with the decision. During the Civil War, Watie accepted a commission as colonel in the Confederate States Army and raised the First Regiment of Cherokee Mounted Volunteers. (Watie became principal chief of the western Cherokee when Chief John Ross abandoned the Confederacy.) Watie successfully harassed Union forces and captured the Union steamboat, J.R. Williams. He was promoted to brigadier general in May, 1864.

Ely S. Parker was born in 1828 on the Tonawanda Indian Reservation (Seneca nation) in New York. Parker became a successful engineer and received an appointment from the Treasury Department to oversee the construction of a custom house and marine hospital in Galena (Illinois). There he met Ulysses S. Grant; during the Civil War, he served on Grant’s personal staff and became his military secretary in 1864. (Parker copied the terms of surrender given to Robert E. Lee at Appomattox.) When Grant became president of the U.S., he appointed Parker as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the first Native American to hold that position.

Native American Participation in the Civil War

Nearly 8,000 Native Americans joined the Confederate army to serve during the Civil War. The Confederacy actively pursued Native Americans to join its cause against the Union, and signed several treaties with members of the Five Civilized Tribes. Native Americans also chose to support the Union and joined its army as well, but they were not recruited with the same focus and enthusiasm.

Union leadership relocated the country’s current soldiers serving in Indian Territory to what they considered more critical areas, leaving this vast expanse of land wide open for skirmishes. The Union’s abandoned forts were immediately appropriated by the Confederacy, which was also anxious to use the Territory as a buffer zone for Texas and Arkansas, a possible link to the western part of the U.S., and a resource to mitigate the consequences of a possible Union blockade.

Though Indian Territory did not suffer combat on the magnitude and frequency of Confederate states like Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia, several important clashes occurred:

* Battle of Round Mountain

* Battle of Pea Ridge

*Battle of Honey Springs (the largest in Indian Territory). This battle occurred in July, 1863 and resulted in a decisive Union victory which gave it control of Indian Territory.

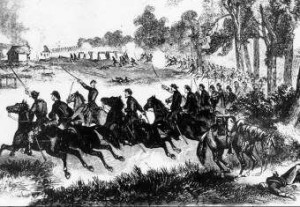

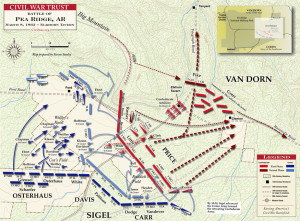

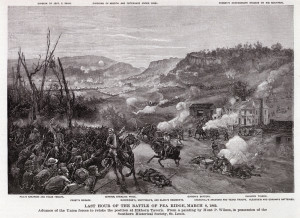

Battle of Pea Ridge

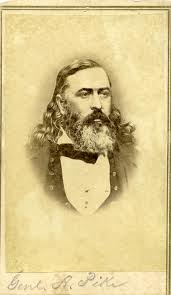

Knowing that Native Americans were bound to have little loyalty to the United States, the Confederacy wanted to enlist their aid during the Civil War (see last post). In 1861, Brigadier General Albert Pike was assigned to the Department of Indian Territory and charged with recruiting and leading Native Americans disaffected with the current Union government. Pike believed that his Indian recruits would serve best while remaining in Indian Territory, but his superiors ordered him to bring 2,500 men into Arkansas. Pike brought a force of about 800 or 900 men and subsequently engaged in the Battle of Pea Ridge (March 6-8, 1862). Very little went well for him in this clash, and the action may have served to show Confederate leaders that attorneys without military experience do not make good generals.

Pike and the Cherokee troops surprised a two-company column of Iowans and successfully routed them early in the battle. The Confederate soldiers celebrated jubilantly, throwing the area into confusion. During the confusion and emotional turmoil of the battle’s aftermath, Cherokee troops scalped at least eight Union soldiers. Later, Generals Benjamin McCulloch and James McIntosh were killed during the battle. Colonel Louis Hébert brought a large force of about 2,000 men to the battle, but got lost in the woods in a poorly executed drive against outnumbered Union forces. Because of poor leadership, General Pike did little to keep the Rebel force moving toward victory. The battle was decisively lost to the Union, and this loss contributed to Missouri being secured for the Union. Pike resigned his commission in 1862 and was indicted in Federal court for inciting war atrocities.

(The Battle of Pea Ridge was also called the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern.)

The Enemy of My Enemy

Native Americans resisted white encroachment on their lands and cultures in a variety of ways (see last two posts). They refused to cooperate with these intruders, refused to send their children to their schools to learn new ways, and held on to their traditions by many strategies. One other significant way Native Americans resisted settlers was to join forces with their enemies. This occurred during the Seven Years War (1754-63) when Britain and France fought over New World territory with the help of native peoples on both sides.

By the time the American Civil War began, Native Americans had had experience with the treachery and false promises of the federal government. Officials in the Confederacy approached various native peoples to remind them of this, offering them better opportunities under Confederate rule for their help in fighting Union forces. The Confederacy created a Bureau of Indian Affairs in March, 1861 and appointed David L. Hubbard as its commissioner. In 1861, the new country’s leaders commissioned attorney Albert Pike as a brigadier general and assigned him to the Department of Indian Territory. There, he was to raise regiments among the Indians and command them in battle. My next post will discuss Native Americans and the Confederacy further.

Other Forms of Resistance

Parents who did not want to send their children to boarding school could not always fight back, but many parents tried to instill the traditional ways and values of their culture into their children despite the federal government. When children returned to their reservations, they could still attend dances and ceremonies, speak their native language (if they still remembered it), wear traditional clothing, hear the old stories, etc. Some, of course, rejected the old ways, but many were willing to incorporate them into the new knowledge and way of life they had seen off-reservation.

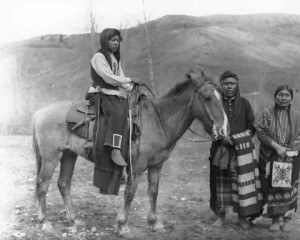

Elders in some tribes did all that they could to keep tradition intact. Around the turn of the twentieth century, the Taos Pueblo required men to wear their hair in braids and wear traditional clothing. If they wore “American” pants, they had to cut the seat out and wear a blanket around the middle; this outfit resembled deerskin leggings and the breech clout. Purchased shoes had to have the heels cut off to resemble moccasins.

Children who refused to grow their hair long once they returned from school or who wore “American” clothes, could be fined one to five dollars. If they refused to participate in dances they were given the alternative of a ten-dollar fine or a dollar-a-stroke whipping in the plaza.*

*These details are taken from Masked Gods: Navaho and Pueblo Ceremonialism by Frank Waters.

Resistance to Boarding Schools

Boarding schools hundreds of miles away from reservations served as a primary tool for the federal government in its attempts to assimilate Native Americans into Anglo culture. By taking children from familiar environments and immersing them into a new one, administrators hoped to break family bonds, alienate children from their cultural pasts, and prevent them from learning native ways from older adults on their reservations.

Of course, parents resisted these efforts. Many refused to give their permission to send children to schools when they had that option; otherwise they hid their children or taught them a “hide and seek” game to play when federal authorities arrived. In turn, authorities were willing to play hardball with the parents. One group of 19 Hopi men were sent to the U.S. military prison on Alcatraz when they refused to give up their children.

Despite their parents’ best efforts, thousands of children were forced to go to boarding schools. Parents were sometimes coerced by threats or the withdrawal of rations into signing permission to allow their children to leave home. Sometimes, however, federal agents actually kidnapped children from their homes.

Schooling Considered Essential

Immigrants to the New World almost always considered their cultures superior to that of Native Americans. As these newcomers spread westward, they became determined to “uplift” native peoples into their own beliefs and customs. Met with the Native Americans’ unexpectedly tenacious resistance to this subjugation of their various cultures, the federal government saw schooling as the best tool at its disposal to gain its objective.

By the 1860s, the federal government had set up 48 day schools on or near reservations to further its goal of native assimilation into Anglo-American culture. The schools’ purpose was to not only educate Native American children about white culture and customs, but to also educate the children’s parents.

Native American resistance to these schools will be the topic of my next post.

All in the Blood

Older methods of curing illness often included bloodletting, the practice of purposely lancing a patient’s flesh in order to get blood flowing. Quantities extracted could be quite small or surprisingly voluminous, depending upon the individual doctor’s beliefs about its effectiveness. Many doctors nearly bled their patients to death, and this type of aggressive, “heroic” medicine fell out of favor during the nineteenth century. Continue reading