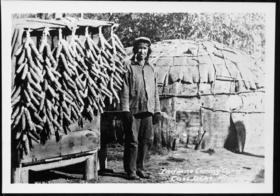

As harvest time grows near, all peoples who cultivate the land hope for good crops. Today’s technology can help farmers produce great quantities of food, but that doesn’t mean that older techniques were not as good–or better–on smaller scales. Native Americans were the New World’s farmers, and they were better at it than history generally credits them. They knew about companion planting for pest deterrence, for instance, and the well-known “three sisters” method of planting corn, squash, and beans used the attributes of these plants to add nitrogen (from beans) to the soil while using corn to trellis them and squash leaves to provide shade for the first two.

Over-tilling Was a Major Contributor to the Dust Bowl, April 1938, Dallam County, Texas, courtesy Three Lions/Getty Images

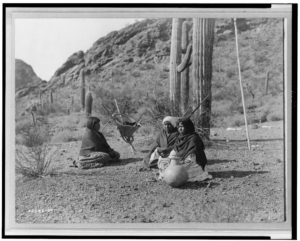

Native Americans also used a “no-till” method, which the USDA is now encouraging all farmers to use. Instead of plowing up acres of land and destroying the soil ecosystem in the process (along with encouraging soil erosion and poor water absorption), no-till farming disturbs the smallest area possible needed for planting. Home methods might include using raised beds or straw bales to garden, or digging individual holes for plants or seeds. Plenty of mulch suppresses weeds and keeps the ground moist. Larger farmers switch from plows to no-till planters; these create narrow furrows in which to plant seeds, and leave the rest of the soil intact.