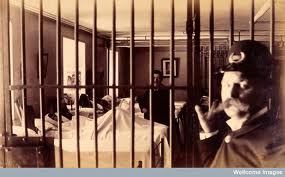

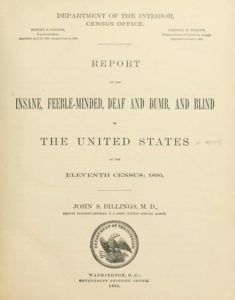

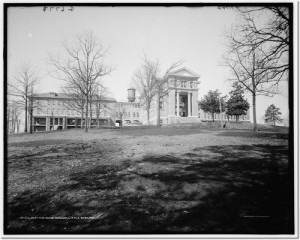

One of the immediate issues facing insane asylum superintendents was their initial lack of status. The term “mad-doctor” had little to recommend it as an indication of learning and professionalism. Even the term “alienist” did not convey to the public the intricacies of helping disabled minds. To enhance their stature, these early psychiatrists found it helpful to band together in professional groups.

The American group first communicated with each other informally through letters. Then a group of thirteen insane asylum superintendents met in 1844 to share information and exchange ideas about the treatment of the insane. They named their group the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane.

German psychiatrists united as a professional body in the Association of German Mad-doctors in 1864, though the General Journal for Psychiatry and Psychic-forensic Medicine had begun publication in 1844. The British organized the Psychological Society in 1901. They changed their name to the British Psychological Society in 1906, to avoid confusion with another organization of the same name.

These early societies were successful in gaining stature for their profession. Many alienists began to testify as expert witnesses in public trials, and the public in general felt safe in relying on their judgment.

______________________________________________________________________________________