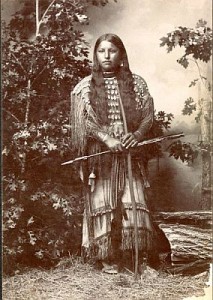

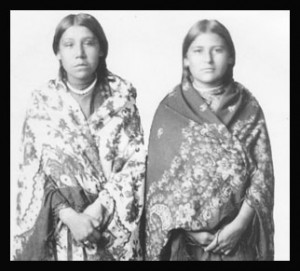

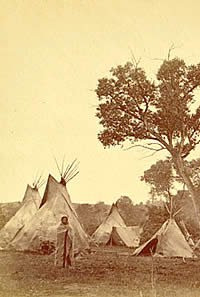

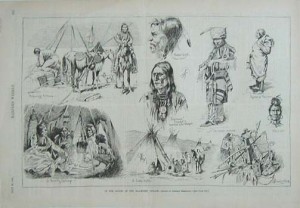

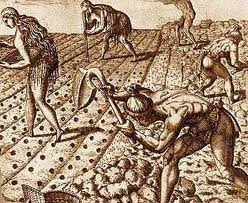

Native American women not only shared political power with men, they sometimes shared in their tribe’s fighting. Though they were certainly not common, female warriors joined in warfare when necessary. Running Eagle became a Blackfoot warrior after her husband was killed, and led many successful raids on Flathead horse herds. Many warrior women entered battle because they had accompanied husbands or other male relatives into a conflict, but Chilhenne-Chiricahua Apache woman, Lozen, decided to become a warrior at a young age. She trained with her brother and developed the gift of finding the enemy. She went by herself to a deserted place and stood with her arms stretched, palms up, to the sky. She turned slowly until a tingling in her palms alerted her to the direction of the enemy’s presence. Lozen was a skilled warrior and scout in addition to acting as a guide to the enemy’s whereabouts.

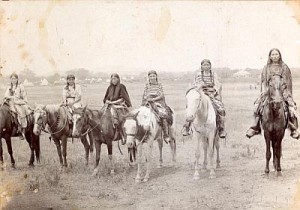

Unlike Lozan, most women didn’t pursue warfare as a way of life, though they could do so without censure if they wished. But, childless married women often accompanied their husbands into battle zones; this proximity to fighting could bring them into an active role in a conflict, particularly if a husband were killed. Women were often leaders in deciding when a tribe would go to war, and in deciding when to end it. They often decided the fate of prisoners, as well. Women could sentence a prisoner to torture or death, or spare his life. After a battle, women also took a share in the spoils.

______________________________________________________________________________________