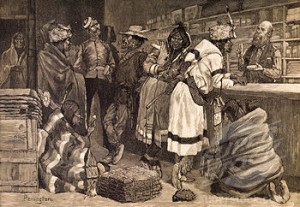

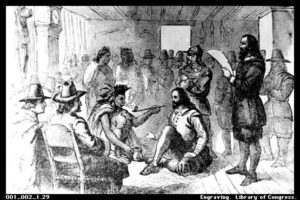

Trade usually benefited both parties in an exchange, since value (of goods traded) is in the eye of the beholder. However, from a strictly economic standpoint, European traders came out well ahead of their Native American counterparts. Except for guns and powder, Europeans exchanged relatively inexpensive trade goods like pots and pans, beads, and cloth for Indians’ furs, which took an entire season for hunters to amass. Europeans were dependent on Native Americans for the furs which had been almost depleted in Europe. However, because they weren’t aware of the European situation, Native Americans couldn’t always leverage their goods to better advantage.

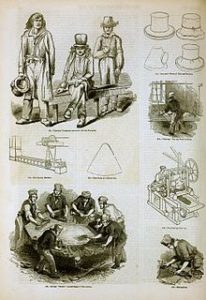

The fur trade was fueled to a surprising extent by men’s fashion. Beaver-felt hats were particularly in vogue during the late 1600s and 1700s, and so many beaver were procured for their pelts that hunting areas were exhausted in certain areas in the New World even before 1700. European fur traders ranged further and further looking for fur suppliers, which led to exploration, cultural exchanges, and warfare. By the middle of the 1700s, European goods had been introduced–and readily accepted–into most native peoples’ lifestyle. In certain areas like the Great Lakes, nearly all Native American men owned muskets or rifles, and women relied on metal cookware and European cloth. The fur trade began to dwindle when animals became scarce or disappeared due to over-hunting, and when silk hats became fashionable in Europe.

______________________________________________________________________________________