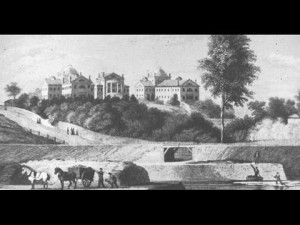

The Oregon State Hospital in Salem, Oregon was created in 1880 by an act of the state’s legislature, and opened its doors in 1883 to 370 patients. By 1896, the number of patients had grown to 1,106.

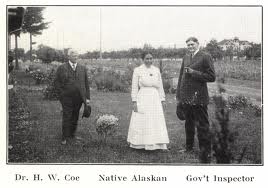

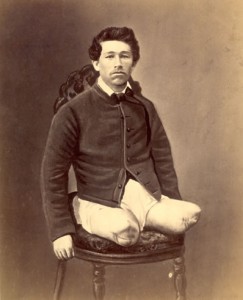

On January 16, 1901, the U.S. government entered a contract with the hospital to house the insane of Alaska at $20/month for each patient. The contract was renewed for an additional year, but in 1904, Alaskans with mental health care needs were sent to Morningside Hospital in Portland, Oregon. They were typically arrested and convicted on insanity, then transported by dog sled and boat to Oregon. Like American Indians, many of these patients were railroaded into an institution because they were inconvenient to someone in power.

The care for the Territory of Alaska’s native population fell under the Secretary of the Interior, as did care for American Indians. Because there were no facilities in Alaska to provide for the mentally ill , they were brought–often unwillingly–to the mainland for treatment under the care of the Sanitarium Company of Portland, Oregon. The hospital was understaffed and relied on drugs to keep patients subdued and manageable.

________________________________________________________________________