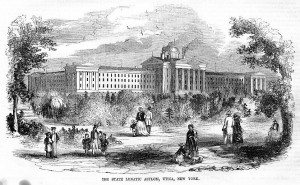

Dr. Hummer found it difficult to keep good help at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. Though part of the problem resulted from Hummer’s bad temper and difficult personality, another part lay in the nature of the work. Attendants in particular had a hard time. They were supposed to be on duty from 6:00 a.m. until 9:00 p.m., though on alternating nights they were allowed to leave at 6:00 p.m. However, they couldn’t leave the premises without Hummer’s permission.

Attendants had a detailed list of 36 specific duties, though they were supposed to do just about anything required of them. A new patient always presented additional work. Attendants were to conduct new patients to their wards and search them for valuables and weapons, make a note of all their clothing, mark the pieces, and then take on the care of the patients’ clothing. They were also to bathe the new patient upon admittance and examine him or her for vermin, marks, or bruises.

The next post will discuss attendants’ daily duties.

______________________________________________________________________________________