Most accounts of assaults within insane asylum walls concern assaults on patients. However, asylum duty held dangers for staff, as well. On October 15, 1878, The New York Times published a vivid account of an assault on an attendant. Only three months on the job, Richard T. Harrison was beaten so badly by a patient at Ward’s Island Insane Asylum that he died within six hours of the attack. Continue reading

Doctors and Nurses

Doctors at insane asylums were recognized authorities in their fields, and most believed they should have total control of their institutions. They expected the utmost deference from staff, including their nurses. Dr. Harry Hummer had many problems with his staff, not only because of his egocentric personality, but also because of his own background and training. He had come from a large institution whose staff interaction was patterned after the etiquette and tradition of the military; he also had servants and “colored” help to whom he could speak as he wished. When he got to the more independent-minded West, his staff resented his high-handedness and bad temper. Some were terrified of Hummer, but others actively spoke against him.

When discontent at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians prompted a thorough inspection, supervisor Charles L. Davis discussed the reasons behind some of Hummer’s problems. “He is fully imbued, as are many others who have never been east [Davis’ error] of the Allegeheny [sic] mountains, that the people of the central west are an uncouth,- ill-mannered and ignorant class.” With this attitude at the ready, Hummer could not help but rub his staff the wrong way.

Davis continued, “He has also evidently been accustomed to speaking to the help about his home and possibly in the hospital where he has served in the manner of master to servant, and has maintained a similar matter of address toward his employees.”

Not much in Hummer’s background and personality boded well for harmony within the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Nurse Training

The Women’s Hospital of Philadelphia, established in 1861, began a training program for nurses in 1863. It is probably the first in the country to have offered any kind of formal training in the profession. The New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston was founded in 1862, and established a school for nurses in 1872; this school is generally considered the first nursing school in the country. Linda Richards (1841-1930) was one of the first students to enroll in the New England Hospital’s school, and became the country’s first formally trained nurse when she graduated in 1873 from its year-long program. Also in 1873, three more nursing schools were established: the Bellevue Hospital Training School in New York; the Connecticut Training School in New Haven; and the Boston Training School in Massachusetts General Hospital.

Even after female nurses were accepted by the medical establishment, they were often seen as workhorses more than professionals. Student nurses learned their profession at hospitals rather than universities and for the most part, represented cheap labor to these institutions; during their training, they swept, mopped, dusted, washed dishes, and performed many other menial tasks. Even when they moved on to more clearly medical duties, they still had little scope for independence. They might sterilize equipment, make up boxes of bandages, sharpen needles, and dress bandages, but all of this work was done under close supervision. Doctors expected complete deference to their decisions and authority.

Bessie Simpson With Supply Cart at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, courtesy Jamaica Plain Historical Society

Nursing Students at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, courtesy Jamaica Plain Historical Society

______________________________________________________________________________________

Gender Issues

Like blacks (see last post), women found it hard to enter the medical profession; in the U.S., women were kept out of hospitals almost entirely until the strain of caring for the wounded during the Civil War showed how valuable they were. Though a sprinkling of female doctors gained attention during the mid to late 1800s, most females in medicine were nurses. However, most did not consider work in mental institutions, where patients could be violent and destructive. Asylum nurses were usually men during much of the 1800s, though married couples sometimes worked together in wards. When female nurses did begin to work at large institutions, they did as much grunt work as compassionate care. Nurses were often expected to sweep and mop their wards, and perform many other housekeeping tasks. It is little wonder that they wanted and accepted help from patients. They had little time off, and were expected to follow doctor’s orders without argument.

By the turn of the century, alienists began to rethink their position on the use of female nurses in asylums. An article by Dr. Charles R. Bancroft (medical superintendent at New Hampshire State Hospital) in the October, 1906 issue of the American Journal of Insanity discussed how to use female nurses effectively. The author believed that it would be best to follow the example of regular hospitals, which gave head nurses both responsibility and authority. “There must of necessity be men attendants, but their position should be that of the general hospital orderly whose duty it will be to execute the orders of the head nurse,” said Bancroft. The doctor displayed both chauvinism and insight when he stated: “Woman are naturally better housekeepers than men,” and later, “. . . they are better nurses than men, but their qualifications never show for what they are worth unless the women are in the superior position.”

Infirmary Nurses in a Toronto Insane Asylum, circa 1910, courtesy Queen Street Mental Health Centre, Archives of Ontario

______________________________________________________________________________________

Segregated Medicine

Though white doctors sometimes had a poor education and few skills, they did not face the discrimination that African-Americans trying to enter the medical field did. In the U.S., black medical students generally went to missionary schools or proprietary schools (owned by doctors who were paid through student fees), or to schools in Canada. Even the few northern schools in the U.S. that would accept black students typically treated them shabbily. Black physicians did not have admitting privileges to hospitals, and because of this, many black patients preferred white doctors.

Many black medical students attended Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., established in 1868. It was named for Major General Oliver O. Howard, a Civil War officer who was helped found the university and who was the commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau. (Howard University received much of its financial backing from this agency.) Whites controlled most aspects of the university; it did not have a black president (Dr. Mordecai Wyatt Johnson) until 1926. However, Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta, a free-born African-American from Virginia who attended Trinity Medical College in Toronto, was among the university’s founding staff. He was the first African-American to serve on a medical school faculty in the U.S.

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (1856-1931) founded Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses (Chicago) in 1891; it was the first black owned and operated hospital in the United States. He also founded the National Medical Association in 1895, after black doctors were excluded from the older American Medical Association. This organization was originally known as the National Negro Medical Association.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Medical News

Medical ads in the early 1900s were imaginative, and sometimes a bit deceptive. Many were disguised as news articles that led readers to think they were getting a legitimate story, only to discover that a medical “cure” was at the heart of the piece. Continue reading

Turn of the Century Medical Advances

Though there was still little that doctors could do to cure insanity or even alleviate its symptoms, there were advances in the medical field. A vaccine for typhoid fever came out in 1896, and was followed by a vaccine for plague in 1897. Karl Landsteiner explored the issue of blood compatibility and created a system of blood typing in 1901. Continue reading

More Study on Insanity

Some Ocular Manifestations of Hysteria, Walter Baer Weidler, 1912, courtesy Wellcome Institute Library

As Freud and other medical men tried to delve into the treatment of insanity (see last post), another group of experts had already made inroads into the blossoming field of early psychiatry. Asylum superintendents were mainly concerned with the management of asylums and how they could help patients within asylum walls. Though treatment in the early years of asylum reform recommended that patients have regular talks with knowledgeable physicians, overcrowded facilities eventually made that impossible. Superintendents had to focus on how schedules, work, and medicine–within the confines of the asylum community–could best be used for patients’ treatment and management.

Some physicians believed that insanity arose from problems within the nervous system. They were confident that study and research would develop new treatments for insanity that would be much better than the care most patients received in asylums. These new doctors were called neurologists. Eighteen neurologists in the U.S. formed the American Neurological Association in 1875, and used the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease as its mouthpiece. They focused on scientific methods and discoveries, versus the sometimes nebulous criteria old-school alienists used as a basis for diagnosis and treatment.

In an article in the March, 1902 issue of the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, author F. Savary Pearce discussed a case of hysteria in a 17-year-old girl. She had stopped eating, believed that x-rays were being used upon her, and that “blood had been taken from her head and that her head had been ‘sewed up’.” The doctor caring for her isolated her from her family, force-fed her through a stomach feeding tube, and gave her static electricity treatments and massage.

She apparently improved greatly under this treatment, which was not much different (if at all) from what she would have received at an asylum. At the end of his article and after a longer discussion of hysteria and its treatment, Pearce recommended institutionalization for cases which did not clear up within about thirty days, or when patients appeared suicidal.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Getting to the Core of Insanity

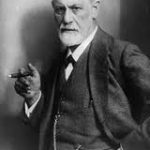

When the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians opened at the end of 1902, scientists and researchers were already striving to find ways to treat insanity other than by confinement in an asylum. Sigmund Freud, born in Moravia in 1856, was one of many scientifically-minded academics interested in mental health who did not necessarily want to become traditional, asylum-connected alienists (the nineteenth-century term for mental health specialists). He enrolled in the University of Vienna’s medical school in 1873, and received his medical degree in 1881. He decided to make a career in medicine with a specialty in neurology.

At the time, “hysteria” was a catch-all term for a host of physical symptoms that doctors felt likely originated in the mind. After studying in France with Jean-Martin Charcot, a neurologist researching the use of hypnotism, Freud became interested in the use of hypnotism to treat hysteria. Freud used the technique in his practice, but eventually felt that the procedure couldn’t ensure long-term success. He instead became intrigued with a treatment devised by a medical school colleague, Josef Breuer. Breuer had discovered that allowing hysterical patients to talk freely often abated their symptoms.

Freud came to believe that most neuroses originated from deeply traumatic events. Allowing patients to confront and discuss these traumas (in safe conditions) proved beneficial and relieved symptoms. Freud found that drugs and hypnosis weren’t necessary for the treatment to be effective; just allowing someone to get comfortable and talk was all that was needed. His “talking cure” proved popular with the public, who found much to like about its gentler approach–as opposed to a stay in an asylum. In 1906, Freud and seventeen other men formed the Psychoanalytic Society, which soon fell apart due to the divergent paths members took as they continued to study mental health.

______________________________________________________________________________________

TB and Native Americans

Though TB existed in the pre-Columbian Andean population, there doesn’t seem to be any definitive proof that TB existed in the continental U.S. before Europeans arrived. (Some skeletal remains indicate that it could have existed, however.) What we do know is that explorers and early settlers brought the deadly infection with them, and then spread it to Native Americans. Once Indians were relocated and forced to live on reservations in the 18th and 19th centuries, the disease became much more prevalent.

TB is especially difficult to control when people are crowded together, since the bacteria can live in exhaled breath and transfer to a healthy individual breathing nearby. Crowded reservations and boarding schools became hotbeds of disease, and by the late 1880s, Native Americans had the highest mortality rates from TB ever recorded–ten times the rate of Europeans during their worst epidemics.

Indian Health Service Nurse Showing X-Ray and Explaining TB Treatment to Members of Navajo Nation, courtesy Library of Congress

______________________________________________________________________________________