Native Americans fought in WWI for many reasons: proof of their loyalty to America, a desire to go overseas, ties to friends and family who volunteered, a desire to fight and prove their manhood (as many young men at the time wanted to do), and for a myriad of other reasons. Though a few all-Indian units did exist within the army, military leadership at the highest levels wanted full integration. Continue reading

Unbreakable Codes

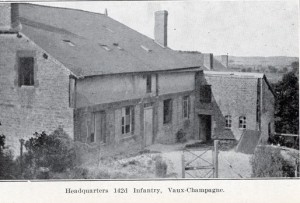

Navajo Code Talkers in WWII have received at least a measure of recognition for their great contributions to that war effort, but the Choctaw Code Talkers of WWI have received far less recognition. In 1917, a group of young Choctaw men began to use their supposedly antiquated and useless language to confound German eavesdroppers. Toward the end of the war when Germans routinely tapped into Allied radio and telephone communications, no code seemed unbreakable. However, Choctaw soldiers in France used their native language to negotiate a troop withdrawal that went undetected by the enemy. That success led to more Choctaw men becoming involved with coded transmissions in their language. Eventually nineteen code talkers contributed immensely to the deception of German eavesdroppers.

Germans were adept at breaking codes, but they had no background for breaking codes based on Native American languages. Traditional military codes were based on European linguistic frameworks, which Native American speakers did not necessarily share. Native Americans didn’t even have words for some essential military terms like “artillery” and “machine guns.” Instead, they called the former “big gun” and the latter “little gun shoot fast.” The Choctaw Nation’s service was highly valuable in turning the tide against Germans during the latter part of WWI.

Ironically, Choctaws (and most other Native Americans) were not U.S. citizens.

______________________________________________________________________________________

WWI Christmas

WWI (1914-1918) led to the death or wounding of 25 million people. It was the first true intercontinental conflict and introduced other firsts to the world of warfare: large-scale mechanical and chemical weapons and the aerial bombing of both soldiers and civilians, among other tragic innovations. Continue reading

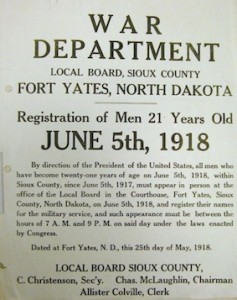

Native Americans And WWI

Many people are familiar with the military contributions of Native American Code Talkers during WWII, but don’t know about Native American contributions to the Great War. Over 17,000 males registered for the draft, but many other men volunteered to enter the military. Data on these volunteers are not as firm, but perhaps half of all Native Americans who enlisted were volunteers. Proportionally, as many or more Native Americans served in the military as other adult American men. Tribal participation rates varied: Oklahoma tribes entered the military at the highest rates, while Navajo and Pueblo men served at the lowest.*

Students from Indian boarding schools like Carlisle volunteered in great numbers, which may have been due both to their familiarity with the military from their school experience as well as a desire to get away from the boarding school environment. Almost without a voice of dissent, whites in authority over these students–all the way up to commissioner of Indian Affairs, Cato Sells–approved of this massive exodus into the military. They attributed it to the success of the Indian Office’s assimilation policy and patriotism on the part of students. Both these factors may have entered into student decisions to enlist, but a thirst for adventure and an equally powerful hatred of their substandard schools were probably just as contributory. Unfortunately, some of these enthusiastic students were underage, with teachers (as the only adults even able to stand in as pseudo-parents) usually turning a blind eye or actually encouraging enlistment.

*Statistics about Native American participation in the military during WWI are taken from Russel Lawrence Barsh’s “American Indians in the Great War; Ethnohistory 38:3 (Summer, 1991).

______________________________________________________________________________________

The Nation at War

In the early 20th century, Americans tended to be isolationists when it came to foreign policy. For the most part, WWI looked like a European conflict into which America need not enter, and president Woodrow Wilson pledged to keep the country out of the conflict. However, after Germany continued to attack unarmed merchant and passenger ships the U.S. severed diplomatic ties with it. Continue reading

Doing Their Part

During WWI, the U.S. government raised money to support its war efforts through Liberty Bonds. Private citizens could purchase bonds, and after the war redeem them for the purchase price plus interest. The government issued four sets of bonds:

* The Emergency Loan Act (April 24, 1917) which set interest rates at 3.5%

* The Second Liberty Loan (October 1, 1917) which set interest rates at 4%

* The Third Liberty Loan (April 5, 1918) which set interest rates at 4.5%

* The Fourth Liberty Loan (September 28, 1918) which set interest rates at 4.25%

Several patients at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians purchased Liberty Bonds. As superintendent and chief disbursing agent for the asylum, Dr. Harry Hummer kept track of who held bonds, and their value. In a letter to the commissioner of Indian Affairs dated May 16, 1918, he listed the Second Liberty Loan Bonds held by patients. Kittie Spicer, Josephine Wells, Davis Roubideaux, Frederick Charging Eagle, Willie McCarthy, Luke Stands-by-Him, Robert Thompson, Joseph Marshall, and Edward Hedges owned bonds valued at $1,350 dollars on which $27 in interest had accrued.

______________________________________________________________________________________

More Hardship

Volunteers at St. Elizabeths Hospital who Worked With Shell Shocked Vets, courtesy George Washington University

Dr. Hummer faced other difficulties associated with the war effort (see last post), particularly a troublesome personnel shortage. He told the commissioner of Indian Affairs that “it is extremely difficult to fill the existing vacancies and I am compelled to keep two or three employees who should be separated.” Since Hummer was typically just fine with a bare-bones staff, his situation at this point was dire; in August, 1918, he had only one male and one female attendant on staff (he should have had three of each). Hummer suggested an increase in pay as a possible solution to his problem, to $40/month with board and lodging for male attendants, and $35/month with board and lodging for females.

A project near and dear to Hummer’s heart also gave way to the war effort: the Indian Office denied his request for an epileptic cottage. This was partly because the asylum still had some vacancies and didn’t seem to need additional rooms. More importantly, as the assistant commissioner of Indian Affairs pointed out, the administration was already in the middle of a huge building program that “will of necessity withdraw carpenters from every section of the country.” Hummer may have been able to counter this with an offer by locals to help with construction, but even he could not argue with E. B. Meritt’s second consideration: there was a need for economy elsewhere in the expenditure of public funds “in order to more successfully prosecute the war.”

Hummer had perhaps anticipated this emphasis on war concerns when he made the following suggestion: “It is possible that the present war will necessitate the construction of another building at this place to care for the insane Indian soldiers or sailors, provided your Office deems this proper.” One way or another, the superintendent wanted additional buildings and patients.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Other Difficult Times

The Depression brought hard times to the country, South Dakota, and the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. The 1930s was not the only difficult period it had faced, though–the Great War (WWI) had also strained the asylum’s capabilities.

All Americans were urged to conserve food and materials, and many stirring posters reminded citizens of how vital their cooperation was to the war effort. Along with the rest of the country, the asylum supported American troops by cutting back on food so that the excess could be sent to soldiers overseas; meatless Mondays were a staple throughout the country. Superintendent Dr. Harry Hummer also initiated other measures to counter “the food situation” brought about by the war. In a letter dated July 4, 1918, Hummer reported to the commissioner of Indian Affairs that he had had to institute “one beefless, one porkless, and one meatless days” each week, along with six extra meatless meals each week. No one liked the new menu, and Hummer reported “a considerable degree of grumbling and discontent among the less patriotic of our employees.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

Staying Afloat

The Great Depression affected all regions of the country, so it’s understandable that townspeople in Canton would fight to keep open any institution that gave employment to its citizens. (See last post.) Townspeople and civic leaders had a history of supporting and encouraging all their local businesses, and some were surprisingly successful even through the dire economic times of the Depression. Continue reading

Difficult Times

The community of Canton had always been loyal to the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. They bragged about it to anyone who would listen and disparaged any criticism of it, pointing to the wonderful write-ups local reporters and other visitors routinely gave when they toured the facility. Citizens wanted their town to grow in both size and prestige, and always hoped that the unique institution in their midst would contribute to that goal. The asylum also meant steady jobs for a number of townspeople, and a market for the town’s goods and services.

During the 1933 battle to shut the asylum down (see last post), however, even more was at stake. The entire country was suffering as the Great Depression worsened, and the asylum now presented an economic lifeline that couldn’t be replaced. Throughout the country, bank failures had wiped out personal savings for many families, who often found themselves homeless afterward. In 1933, a quarter of U.S. workers who sought jobs were unemployed, while hunger and poverty were rampant. A report from December, 1932 shows that (including superintendent Dr. Harry Hummer) nineteen people were on staff at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, and undoubtedly others worked there on small contract projects. When every job was so important, the people of Canton were not about to let the asylum close without a fight.

______________________________________________________________________________________