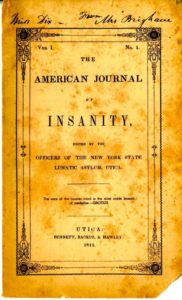

Asylum doctors tried hard to share information about the developing field of psychiatry, and sometimes discussed interesting cases in journals. In the January, 1869, issue of the American Journal of Insanity, Dr. Judson Andrews gave details about a fifteen-year-old-boy brought into his asylum. Continue reading

What Do They Say?

Their own writings provide fascinating insights into the mental health profession’s ever-changing understanding of insanity and how to treat it. Although it was not the only vehicle by which to express current thoughts on the topic, the American Journal of Insanity did have the backing of many authorities in the field. Articles in it ranged from purely practical matters to theoretical speculation concerning the root causes of insanity. My next few posts will give a sampling of what was on the minds of leading alienists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In 1863, Dr. John Bucknill wrote an article, “Modes of Death Prevalent Among Insane,” in which he advocated consistency in the way asylum superintendents registered cause of death. Bucknill found that the term exhaustion served as a catchall word that gave little clue as to the actual disease or condition that took a patient’s life. Reading from asylum obituary tables, Bucknill noted that at one asylum a physician attributed 30% of deaths to exhaustion. “In another report, I find a number of deaths attributed to ‘prostration,’ which is perhaps a synonym for exhaustion; while in another report the terms ‘gradual decay’ or ‘general decay’ appear often to be used to express the same facts.”

The vagueness of words like exhaustion and decay kept asylum physicians from keeping accurate records concerning causes of death among their patients. Bucknill urged physicians to give the names of the disease that killed their patients, and then simply add the precise mechanism that shut them down if they wished. Bucknill gave an example of a patient who died from refusing food because of his delusions. Under the system he currently saw, doctors would say the person died of exhaustion, but Bucknill urged, instead: “Let us say that the patient died of acute mania, or acute melancholia, adding, if we think fit, that the mode of death was anemic syncope from refusal of food.”

Though Bucknill’s concerns might seem trivial today, he was part of a movement to bring consistency and order to a field which had little science or tradition behind it. Because psychiatry was a new field, early practitioners had to hammer out details on such fundamental issues as how to build insane asylums, what to call them, and then how to classify the illnesses they saw within their walls. Actual therapeutic treatment was then another huge issue.

Religious Melancholia and Convalescence, from John Conolly's book, Physionomy of Insanity, 1858, courtesy Brown University

______________________________________________________________________________________

Oversight in Vain

Though the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians did not receive visits and inspections as regularly as most other asylums (see last post), some of the inspectors who visited had a strong sense that something was wrong. When Charles L. Davis inspected the asylum, he found it practically roiling with anger and rebellion, with almost all its employees ready to quit. In a report written in late 1909, Davis determined that Dr. Harry Hummer was not a good choice as superintendent for the asylum. Though quite a number of charges had been made against Hummer by the staff and his own assistant superintendent, Davis did not feel that any one of them quite warranted Hummer’s dismissal from the Indian Service. Instead, he advised the Indian Office that Hummer was simply temperamentally unsuited for his position. “In view of the facts developed through my investigation . . . there is nothing left but to recommend another man be placed in charge of the Asylum,” Davis wrote.

Twenty years later, in April, 1929, the facing sheet (a government form) of Dr. Emil Krulish’s latest report on the asylum said in the subject block: Reports on unsatisfactory conditions brought about by conduct of the supt. Dr. Hummer.” Dr. Emil Krulish ended this short follow-up to a prior inspection with: “. . . I desire to state that my last visit has more fully convinced me that a change in the management of this institution is imperative for the sake of harmony and efficient service.”

Dr. Hummer stayed on.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Long Distance Oversight

Few people ever wanted to enter an insane asylum, no matter how well run or up-to-date it was. And, like all institutions run by fallible human beings, asylums were not immune to mistakes and misjudgments on the part of their staffs. One problem the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians faced that St. Elizabeths and McLean didn’t (see last few posts) came as direct consequence of its long-distance oversight.

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was not under a trustee or board of visitors system like the other two asylums, though it is certainly untrue that this establishment was never inspected or investigated. However, the asylum was managed for the most part from thousands of miles away. The asylum’s superintendent in Canton reported directly to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC, and the seven commissioners who held the position during the time the asylum was open very seldom, if ever, actually visited the place.

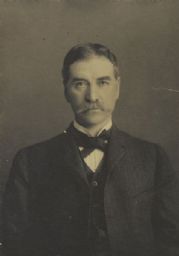

Agents or inspectors from the Indian Office did come by fairly regularly, but none of these men were psychiatrists. They found it difficult to determine how well the patients were being treated for mental health issues, and usually confined themselves to commenting on the state of the buildings and how efficiently the superintendent ran his farming operation. Medical staff from the Indian Office eventually began visiting much more often as the asylum grew in size and came to the notice of the commissioner through complaints. Dr. Emil Krulish became a frequent visitor and made numerous criticisms that honed in on treatment and the way the superintendent, Dr. Harry Hummer, managed his personnel and patients. However, his voice was ignored and Hummer continued to thrive in his position.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Overlooked

McLean Asylum for the Insane and St. Elizabeths were two very different, yet for the most part, well-regulated insane asylums (see last two posts). And though they differed from each other in terms of funding and client base, they contrasted even more sharply with the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. The Canton asylum was a government-funded asylum like St. Elizabeths, and both of these institutions focused on either indigent patients or those of moderate income. What really set the Canton asylum apart from McLean and St. Elizabeths, though, was the difference in oversight.

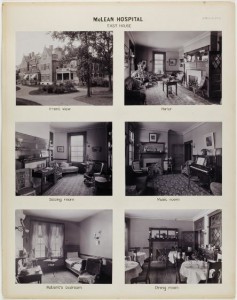

At McLean, trustees watched over the management of the asylum and a Visiting Committee “made it a point to see personally each patient in the asylum once a week, checking his name off a prepared list,” according to the editors of The Institutional Care of the Insane in the U.S.A. and Canada, published in 1916. This extraordinary degree of oversight took place well before 1900, when the facility had one nurse for every four patients. As the asylum grew, trustees could not keep to the same schedule, but they were still intensely involved with the asylum. Even at the turn of the twentieth century, trustees hired eminent architects for additional buildings, and doctors knew their patients and kept detailed histories on them.

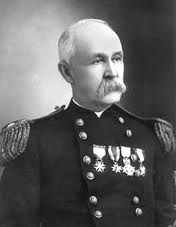

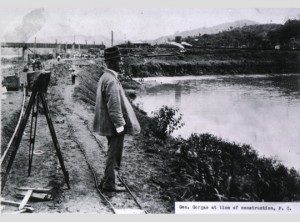

The government hospital, St. Elizabeths, first fell under the scrutiny of a five-member board of charities, appointed by the President of the United States for terms of three years. Additionally, the President appointed a nine-member Board of Visitors. This board included representatives of the military and clergy, and many times included an acting or retired surgeon-general. In 1914, Brigadier General George M. Sternberg, a pioneer in battlefield wound treatment during the Civil War, was President of the Board, and the surgeon generals of the Navy and Army were also represented. The latter surgeon-general was William C. Gorgas, who had been responsible for wiping out yellow fever in Havana after Walter Reed’s discovery of the mosquito vector for it. Though St. Elizabeths had its share of detractors and investigations, that asylum and McLean were typically watched over by prominent locals who took their duties seriously and felt responsible for providing area patients with quality care.

In my next post, I will discuss oversight for the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

William C. Gorgas at the Time of the Panama Canal Construction, courtesy National Library of Medicine

______________________________________________________________________________________

Another Contrast

It perhaps isn’t quite fair to compare a federal insane asylum like the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians with a private institution catering to the wealthy. (See last post about McLean Asylum for the Insane.) However, the government did have another insane asylum, and it was also quite different from the one at Canton. St. Elizabeths had a training school for nurses, quarantine rooms, and a full hospital where operations ranging from appendectomies to hysterectomies were performed. It was one of the first asylums in the country to appoint a pathologist to its staff, and one of the first to institute therapeutic hydrotherapy.

At about the time that the Canton asylum opened, Dr. William A. White arrived at St. Elizabeths. He created a clinical director position, and organized a scientific department which eventually included a pathologist, psychologist, histopathologist, and a number of assistants. The department published their research in the form of an annual bulletin. St. Elizabeths also trained surgeons from the Public Health Service and Marine Hospital Service to work on Ellis Island (helping discover insane immigrants). The hospital shared its research with the U.S. Army and Navy to help bring military psychiatry into their respective branches. The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was much smaller than St. Elizabeths and perhaps couldn’t be expected to do the same things. However, its staff could have done much more research on mental health issues in a unique population than it did, and been much more involved with its peer organizations that it was. Instead, the asylum’s most significant staff member, Dr. Harry Hummer, allowed the facility to stagnate into a backwater institution that helped its patients very little.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Opposing Systems

Though Dr. Harry R. Hummer’s medical and psychological experience did not guarantee the best care for patients at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, at least he had the proper background for the position he held. The asylum’s first superintendent, Oscar Gifford, had no medical training at all. The Indian Office bears exceptional fault for appointing someone without the obvious qualifications to head a medical facility; by 1902, it was nearly incomprehensible that an insane asylum superintendent would not also have a psychiatric background.

In contrast, the McLean Asylum for the Insane in Massachusetts was a premier establishment that catered to wealthy families who could afford to give their loved ones the best of care. Its staff administered typical therapies for the time: calomel, Epsom salts, opium products, and various purges, along with rest and recreation designed to calm patients and help them keep their minds off their troubles. Recreation could include sewing and reading, billiards, tennis, strolls through manicured gardens, carriage rides, trips into town, and art appreciation classes. But, despite its country club atmosphere, between 1888 and 1892, McLean established laboratories that combined biological chemistry, physiological psychology, and psychiatry, and were perhaps rivaled by only Professor Emil Kraepelin’s laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Putting a Name on It

Interest in mental health and how to care for the mentally ill heightened as time went on and professionals became more immersed in studying the intricacies of the mind and human behavior. In the United States, by the turn of the twentieth century large asylums were still the tool of choice for helping the insane become well, or for dealing efficiently with the chronic insane. As mental health specialists made advances in treatment, they continued to look at ways to present themselves and their work to the public in a positive way.

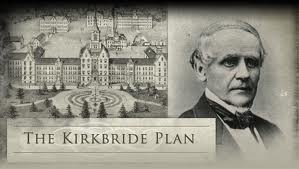

In 1854, the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Asylums for the Insane (AMSAAI) debated on what terms they should use to even describe the buildings where their patients lived. Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, a pioneer in asylum architecture, presented a paper at the AMSAAI’s ninth meeting: “On the Importance of Precision and Accuracy in the Use of Terms for Insanity and Instructions for its Treatment.” In it, he objected to worlds like lunatic, asylum, retreat, keeper, and cell to describe anything within the walls of what were commonly known as insane asylums. In many people’s minds, the word “hospital” was only a place for paupers and outcasts, so it was not suitable, either. “Insanery” seemed suitable to one doctor discussing the paper, since it resembled the British word “infirmary.” This particular alienist (mental health specialist) did not especially object to the terms asylum or lunatic, since the former signified a sacred place or sanctuary, and the latter had been in common usage for a long period.

By 1920, at the seventy-sixth annual meeting of the American Medico-Psychological Association, which had incorporated the old AMSAAI, words like cell and keeper had indeed been discontinued because of their negative connotations. Now the concern at hand was whether or not to change the name of their organization and the way they referred to insanity. In the end, the organization was re-named the American Association of Psychiatrists, and the word psychiatry was substituted for the words “the treatment of insanity.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

Room for the Shell-Shocked

In 1917, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene (see last post) canvased various hospitals to see where soldiers and sailors could be treated for mental conditions created by the war. They naturally turned to government facilities like veterans’ hospitals and the government’s two existing insane asylums. The larger of these latter facilities, St. Elizabeths, was already charged with the care of insane military members. Its superintendent, Dr. William White, submitted his thoughts on the matter to the Secretary of the Interior, saying that a large influx of insane patients would require a correspondingly large increase in facilities. The plan in place was to ask for statutory authority “to distribute the overflow from the present organization [St. Elizabeths] to the several State hospitals.” Using caution before commitment, White asked how many patients might be expected, and whether or not the Secretary wanted them housed in temporary or semi-permanent structures.

Dr. Harry Hummer, superintendent at the government’s other insane asylum, the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, offered his own thoughts about the ability of St. Elizabeths to care for mentally unstable soldiers. He wrote to the commissioner of Indian Affairs: “It occurs to me that with the already overcrowded condition at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Washington, D. C., it will be impossible for the authorities of that institution to care for the rather sudden accession of cases of mental disease which the present war will necessarily entail. . . . . It is barely possible that the federal government will decide that each State shall care for its own insane. In that event it will be necessary for the State of South Dakota to care for its insane, either at the Asylum at Yankton or otherwise.”

Hummer asked the practical question concerning the number of patients who might need care, and provided his own tentative calculations for the commissioner. Hummer estimated that 20-25 percent of South Dakota’s soldiers and sailors might become incapacitated during the war, and that of that number, ten percent would be mental cases. Therefore, he thought that one-fortieth of the men enlisted from the state would need to be cared for at one of its institutions.

Hummer added: “I am sorry that your Office decided that we should not build the proposed epileptic cottage, as this would have given us additional beds which might have been used for the purpose now in question.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

Shell Shock

Professionals and laypeople alike have probably always observed that war could affect those who went through it, both physically and mentally. After the Civil War, some people who tried to put their finger on what had changed with returning veterans, discussed the “soldier’s heart” phenomenon. This was a (usually) negative change they saw in their loved ones, which they were sure came from being in a war and exposed to combat. Observers primarily believed that physical changes in the heart were responsible for the changes they saw in the person, though they also believed that pining away for their homes during their period of service could bring on nostalgia-related mental symptoms. During WWI, “shell shock” was a descriptive term for the physical effects constant bombardment took on soldiers engaged in long bouts of trench warfare, but physicians also recognized a mental component that they termed “traumatic neurosis.”

WWI era medical professionals had enough information about war-related mental trauma (now called PTSD) that they anticipated its occurrence. In 1917, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene formed a task group called “the committee on furnishing hospital units for nervous and mental disorders to the United States Government” which began to canvas likely facilities in which to house mentally ill soldiers. Veterans Hospitals were obvious sites, and the committee also contacted the superintendents of the government’s two insane asylums: St. Elizabeths in Washington, DC and the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians in South Dakota.

My next post will examine their responses.

______________________________________________________________________________________