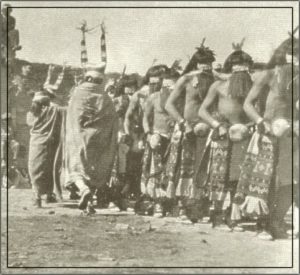

White society saw Native American dancing in two ways: immoral and/or depraved, or as perfectly acceptable cultural expression (see last two posts). Native Americans often pointed out that their dances were not as immoral as white dancing, which included close physical contact as well as uninhibited movements. Continue reading

Why All the Concern?

The controversy over Native American dancing did not arise all at once, of course (see last post). European settlers were often surprised at the energy and freedom inherent in many ceremonial dances, but unfortunately attributed much of it to the “uncivilized” status of Native Americans. Continue reading

Fear of Dancing

Hopi Clowns Next to a Line of Dancers in the Long Hair Dance, 1912, courtesy Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation

Though the federal government wanted to suppress anything that kept Native Americans from assimilating into white culture, dancing seemed to be of special concern. Dances were central to many traditional rituals and ceremonies, and therefore, suspect. Continue reading

More Rules

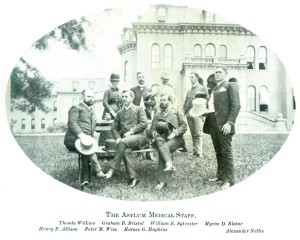

The Indian Office provided rules for attendants working at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians which were thorough and explicit; similar instructions were most likely the case in all other insane asylums. Patients were supposed to “preserve order” but only by using the mildest means possible. Rule 20 stated: “No kicking, striking, shaking, or choking of a patient will be permitted under any circumstances. Patients must not be thrown violently to the floor in controlling them, but the attendant shall call such assistance as will enable him to control the patient without injury.”

This rule was broken any number of times, and at least one male attendant was fired for committing unwarranted violence against patients. Mechanical restraints like cuffs and camisoles (straitjacket) were to be used only with the consent of the physician or superintendent, but employees did not follow this rule. Instead, they got restraints from the financial clerk simply by asking for them. Dr. Hummer, who later received very harsh criticism for the asylum’s excessive use of restraints, either permitted their use (though he often said restraints weren’t used) or he abdicated his responsibilities to the financial clerk. Either way, he had to know that employees were using restraints quite freely . . . unless he wasn’t making rounds often enough to catch it. Whatever the reason for all the restraints, Dr. Hummer was responsible for the situation.

And the Patients’ Side

Employees at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians had clear instructions concerning their duties, including the all-important attendants who were at the heart of patient care. (See last post.) They were charged with keeping rooms neat and clean, attending to their patients’ needs in terms of clothing and personal care–basically what anyone would expect of an institution set up to care for the insane. The reality was often different, and the conditions many patients lived under would have been disheartening.

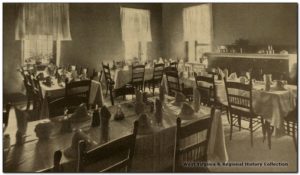

Though foreign to their own experience on or off a reservation, patients arriving at Canton Asylum when it first opened would have walked into a spacious, light-filled building. Electricity and running water might have been exciting to use, and regular meals supplemented by garden produce would have been tasty and welcome. As the asylum deteriorated over the years, however, patient comfort declined. The early structure had been pretty and airy, with pictures on the walls and nice furniture. As time went on, the pictures disappeared; the floors, clothes, and bedding became dingy and worn; and the nourishing food evolved into a monotonous diet of starches and vegetables. Patients used chamber pots instead of toilets, which allowed human waste to create a stench and promote disease in the midst of crowded rooms.

By the time the asylum closed, one inspector likened patient care at the asylum to that of a prison. Patients who had been sent to the institution for mental problems received no mental health care at all–the whole purpose for the asylum. Ultimately, authorities concluded that almost no amount of money could make the asylum function as it should and decided to shut it down.

A Difficult Life for All

Though patients undoubtedly had wretched experiences at most asylums, the life of an attendant was also difficult. Even in the first decades of the twentieth century, it was usual for attendants and other staff (including physicians) to reside at the asylum where they worked. Continue reading

A Patient’s Work is Never Done

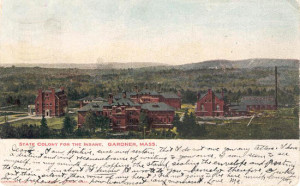

Insane asylums used patient labor for both occupational therapy and cost-containment (see last post). However, that labor didn’t always start after the facility had been completed and simply needed to be maintained. Asylum administrators often brought in patients after only a limited space was ready for occupancy, and then used them to help build the rest of the asylum.

In October of 1902, Governor Crane of Massachusetts declared its newest asylum, the Gardner State Colony, ready to receive patients and admitted five men from the Taunton Insane Hospital. Five more men were transferred from Westborough two months later, and over the winter these male patients worked in the woods to cut down 46,000 feet of lumber. That summer, they worked on the farm and excavated for the asylum’s water supply; in 1904 the institution received 111 patients.

A case can surely be made that patients enjoyed certain types of occupational therapy such as fancy needle-work or light gardening, but tasks such as building roads, chopping down trees, clearing fields, working in hot laundry rooms, etc. were not for their benefit. Though some administrators (and the public) may have seen the practice as simply expecting able-bodied men and women to work for their room and board, there is really no way to know what kind of coercive measures were used to get some of the more difficult and undesirable tasks completed.

Keeping Busy

Insane asylums tried to be self-sufficient, but in our modern era it can be hard to understand just how self-sufficient they were. The Clarinda State Hospital in Iowa was one of many similar institutions that used patient labor for the dual purpose of keeping operating costs down and giving patients something to do. The asylum employed patients (under direction) to sew nearly all the clothing they needed, and to make shoes under the direction of a shoemaker. Patients also engaged in woodworking and made brooms from broom corn raised on the asylum farm. A bit more unusual was the facility’s mattress-making department, where all the new mattresses for the asylum were made.

“Mattress hair is bought and also a good quality of material for the cover, which is made up in the sewing room and afterwards filled by patients. . . . Soiled or worn mattresses in which the hair has become packed are taken apart, thoroughly renovated by steam, dried, thoroughly picked and the hair used over again.”

The writer ended his description of the asylum with the words that: “The general spirit of the institution is to have the asylum idea as much in the background as possible and to supply surroundings and influences as much like those at home as can be made.”

It would be difficult to discover whether this aim had been achieved.

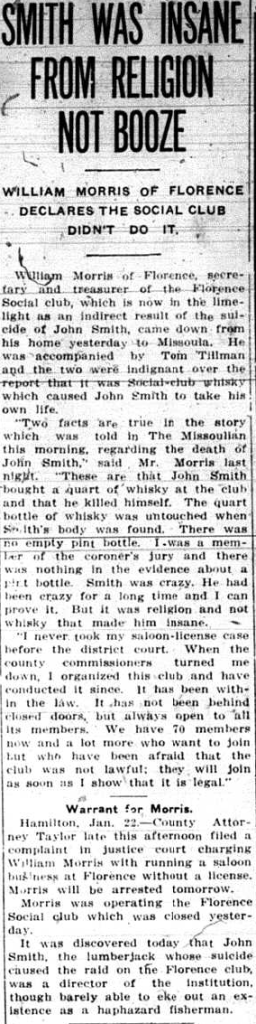

Who Says You’re Crazy?

One of the major problems with the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was that commitment rules were so lax. Like most asylums, there were patients incarcerated because they were inconvenient to others or created problems for civil authorities, but there were also some patients who genuinely needed help. In either case, few patients admitted to the asylum had actually been evaluated by a physician of any kind, let alone one who specialized in mental illness. Instead, they were usually sent to the asylum on the assessment of only a layperson (Indian agent or reservation superintendent) which was terribly unfair. Abuses of power could, and did, take place, because even if these lay persons were actually trying to help someone, they weren’t necessarily right in their opinion of the person’s mental state.

Though abuses of power probably occurred everywhere at times, patients in other states and institutions often had stronger protections. Massachusetts had always been a progressive state when it came to helping its citizens facing mental health issues, and its commitment laws were fairly strict. In 1916, the editors of Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada wrote: “Commitment [in Massachusetts] may not be made unless there has been filed with the proper judge or justice a certificate of the insanity of the person by two physicians nor without an order signed by the proper judge that he finds the person insane.”

The judge could see and examine the person if he thought it needful, could also call in a third physician, and could summon a jury of six men to hear and judge whether the proposed patient was insane or not. Furthermore: “A physician making a certificate of insanity must be a graduate of a legally chartered medical school, in actual practice for three years and for the three years last preceding, and be registered. His standing, character and professional knowledge of insanity must be satisfactory to the judge.”

Though there could certainly be an “old boy” system that would allow a motivated complainant the opportunity to have a family member or enemy committed to an insane asylum, it was still much more difficult for two physicians and a judge to collude against a person than it was for one layperson to decide that an Indian was crazy.

Alienists’ Diagnoses Were Never Foolproof

Alienists’ assessments of their patients’ mental conditions could be suspect at the best of times. They were particularly suspect when alienists dealt with people who did not fit the norms of an Anglo-centric society. Newly arrived immigrants were vulnerable to a misinterpretation of their mental status, and of course, non-English speaking Native Americans could easily be misunderstood or be so frustrated and frightened that they couldn’t communicate effectively. Continue reading